DECOY MAGAZINE: The Art of Deception as Art

Politicians, lovers and merchants have practiced the arts of deception for centuries. But one of the purest forms of the art perhaps originated and certainly blossomed in North America over the past couple of centuries. It's celebrated in Decoy Magazine, a recent addition to the MagSampler.com newsstand.

Carved waterfowl decoys were once purely utilitarian, created to be placed in water and to bob up and down, luring live fowl to join them under the guns of waiting vice presidents and other hunters. Apparently mallards, geese and the like are not stupid, and the more realistic the decoys, the more success the hunter can expect. Many a hunter in America's past was also good with his hands, and the happy result has been a significant number of hand-carved and painted decoys. Our mania for collecting has taken many of these old ersatz birds out of the water and onto mantels or inside display cases.

Decoy Magazine, published bimonthly in Lewes, DE, chronicles the stories of these decoys and monitors the many shows and auctions where they pass from hand to hand, often at what seem to be outrageous prices. In a recent issue editor and publisher Joe Engers notes that the biggest decoy auction house, which runs three sales a year, has reported gross sales in excess of $2 million for each auction over the past two years, with at least one decoy in every sale going for more than $100,000.

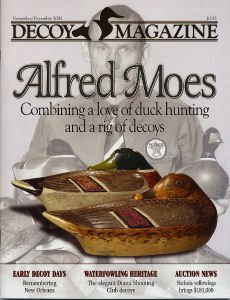

Stories of these decoys, their carvers and their collectors fill the pages of the magazine. The cover article of a recent issue is about Alfred Moes, a strong, silent Minnesotan, son of an expert woodcarver, who ran a gas station and garage in the little town of Lakeville. For some reason, the 44-year-old Moes, an avid hunter, decided in the winter of 1938 to carve a group of mallard decoys, the first he is believed to have made. The 15 decoys he created are now legendary for their craftsmanship and artistic appeal. He never made any more. Some are sleeping, some upright, and some are headless. Can't figure out why they have no heads? Because they're supposed to be feeding, with their heads in the water. It took me a while to get it too. A real mallard sure has to think fast to avoid becoming a dead duck.

A fascinating bit of detective work is reported in the issue. It's about a pair of pintail duck decoys that Bart Woloson, author of the article, picked up at a Milwaukee decoy show. Made from composite ground cork, they feature unusual swinging weights that are supposed to hang from the bottom of the decoy when it's in the water. His only clue as to the origin of the decoys was a patent number embossed on the weights. Research in the patent records led him to discover that a fellow named Anthony A. Oeding, living near St. Louis, patented the swing weight system in 1939. The weights are designed to oscillate in the water and propel the decoy. Google and phone book searches turned up nothing on Oeding, until Woloson found a 1961 newspaper picture that showed the inventor shaking hands with President John F. Kennedy! It turns out that Oeding had just turned 65 and was the 15 millionth recipient of Social Security benefits in the nation's history. The accompanying article provided Woloson with a few facts about the inventor―he was born in 1896 and had worked in an airplane factory―but the frustrated collector still doesn't know if the two pintail ducks in his possession are the only ones that Oeding made.

It's my sad duty to report that one of the articles in the magazine mentions that many modern waterfowl decoys are made of plastic.

An annual subscription to Decoy Magazine (six issues) is $40.00 from the publisher. We'll send you a sample copy for $2.59.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home